Approved by COSEWIC November 2023

Preamble:

The Species at Risk Act defines “wildlife species” as “a species, subspecies, variety or geographically or genetically distinct population…”. This definition gives COSEWIC a mandate to assess units within a recognized taxonomic species. COSEWIC recognizes a unit below the level of a recognized taxonomic species as a Designatable Unit or DU (and, so, as a “wildlife species”) if it has attributes that make it both "discrete" and "evolutionarily significant”. The starting point for consideration by COSEWIC is that each named species in Canada is composed of a single Wildlife Species.

Approach to the identification of DUs for status assessment:

A DU is a unit of Canadian biodiversity that is discrete and evolutionarily significant, where discrete means that there is currently little transmission of heritable (cultural or genetic) information from other such units, and evolutionarily significant means that the unit harbours an evolutionary history or heritable adaptive traits not found elsewhere in Canada.

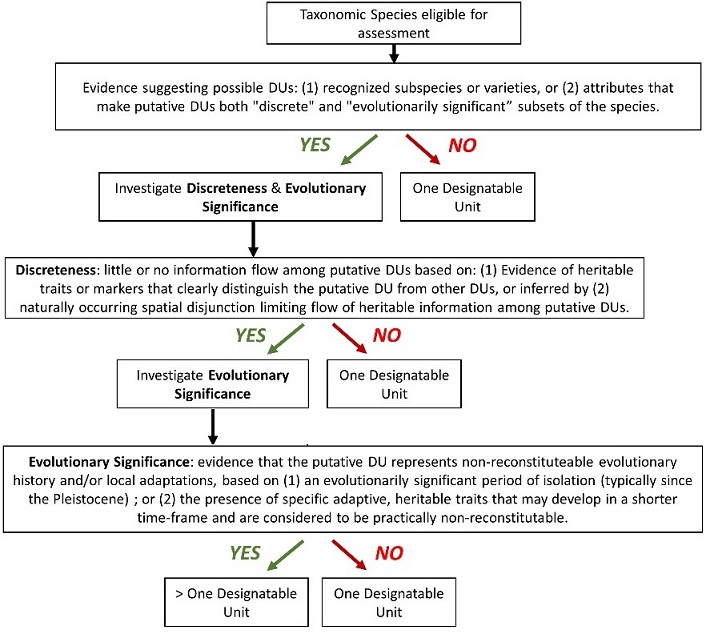

All DUs to be assessed or re-assessed should be examined against the current DU guidelines. Where SSCs believe DU structure is expected to be complex, a stand-alone DU report should be prepared for approval by COSEWIC prior to a status assessment or reassessment. A short summary of this pre-approved DU structure should then be presented in the DU section of the full species status report, along with any new information that could modify the pre-approved DU structure. Figure 1 outlines a simple flow- chart to aid in deliberations.Guidelines for the identification of DUs:

COSEWIC recognizes a DU (i.e., recognizes a unit below the level of a taxonomic species, where these taxonomic species are named by the authorities listed in Appendix E4) as a “wildlife species” if it has attributes that make it both "discrete" and "evolutionarily significant". These criteria need to be met regardless of whether or not the infraspecific unit is named (e.g., as a subspecies or variety) in the literature.

Discreteness

A possible DU may be considered discrete based on one or both of the following criteria, each of which indicate little transmission of heritable information between it and other DUs:

D1. Evidence of DU-wide heritable (culturally or genetically) traits or markers that clearly distinguish the possible DU from other DUs (e.g., evidence from genetic markers or heritable morphology, behaviour, life history, phenology, migration routes, vocal dialects).

D2. Natural (i.e., not the product of human disturbance) geographic disjunction between possible DUs such that transmission of information (e.g., individuals, seeds, gametes) between these "range portions" has been limited for sufficient time that discrete units are likely to have arisen (e.g., via genetic or cultural drift) as defined in D1.

Significance

If a possible DU is found to be discrete, its evolutionary significance can be assessed. A DU is considered significant based on one or both of the following criteria:

S1. Direct evidence or strong inference that the possible DU has been on an evolutionary trajectory long enough to generate an evolutionary history not found elsewhere in Canada. Such evidence might include phylogenetic data indicating origins in DU-specific Pleistocene refugia.

S2. Direct evidence or strong inference that the possible DU possesses DU-wide (heritable) adaptive traits not found elsewhere in Canada. Evidence might include the persistence of the possible DU in an ecological setting where a selective regime is likely to have given rise to DU- wide local adaptations not found elsewhere. See Practical Considerations/Best Practices below.

Some Practical Considerations / Best Practices

The Discreteness and Significance Guidelines described above are the principles that form the basis for DU delineation. They are meant to be flexible and to be applied by COSEWIC on a case-by-case basis. The practical considerations and best practices described below provide guidelines for report writers and reviewers that COSEWIC will update as needed.

Practical considerations

COSEWIC considers each named taxonomic species in Canada recognised by a contemporary scientific authority to be a single Wildlife Species unless otherwise demonstrated.

DUs should not be identified on the basis of threats or anticipated conservation status. Similarly, DUs are distinct from management units or conservation units, of which there may be more than one within or across DUs.

DUs should be designated following a weight-of-evidence approach (see Appendix C) where different lines and quality of evidence (e.g., genetic, behavioural, morphological, geographic distribution, ecological setting) are evaluated for discreteness and then significance (see Figure 1). Each line of evidence should be considered for the relevant criterion and then the full body of evidence should be evaluated together for discreteness and significance.

Genetic population structure does not necessarily indicate discreteness, as populations can be genetically structured in the presence of ongoing gene flow. However, it is not necessary to establish genetic discreteness between possible DUs if other evidence meets the criteria.

Examples of evidence of “(heritable) adaptive traits” relevant to S2 could include fixed differences in alleles at multiple functional nuclear loci, or clear distinctions among possible DUs in DU-wide functional traits (e.g., stable, culturally transmitted, functional behaviour, such as foraging methods or migration routes). Summary documents outlining the various types, uses, and limitations of genetic and cultural data are available upon request.

The evolutionary significance of a DU reflects the fact that if it were lost, the suite of unique traits the DU harbors (e.g., its full consensus genotype, its full set of morphological, cultural, and behavioural traits) would be lost in Canada. If its entire range had been in Canada, it would be deemed extinct. If it were lost from its Canadian range but still present elsewhere, it would be deemed extirpated.

As a guide for delimiting DUs, the criteria outlined above imply that, while it may be possible for individuals from the same taxonomic species to move (or be moved) into an area formerly occupied by another DU (e.g., one that has been extirpated), these moved individuals and their descendants would belong to the DU from which they originated until they evolved (culturally or genetically) such that they met the Discreteness (under D1) and Significance criteria. One named DU cannot rescue another.

Best Practises

To begin any practical delineation of DUs, one should attempt an initial allocation of individuals or groups of individuals if data permit. This can come from a previous assignment or a delineation based on clusters defined using taxonomy, geography, morphology, genetics, behaviour, or other traits.

When there is more than one existing DU for a previously assessed taxonomic species, SSCs are encouraged to critically examine these DUs against the current DU guidelines, and to do this as early as possible (e.g., during reassessment planning). SSCs may call upon the Chair as needed to provide suggestions on expertise within the wider Committee, within the DU Working Group, or within other SSCs.

Some lines of evidence may be relevant for both discreteness and significance. For example, deep phylogenetic divergence across the genome (indicating separate Pleistocene refugia and little subsequent gene flow) may indicate discreteness (D1) and significance (S1).

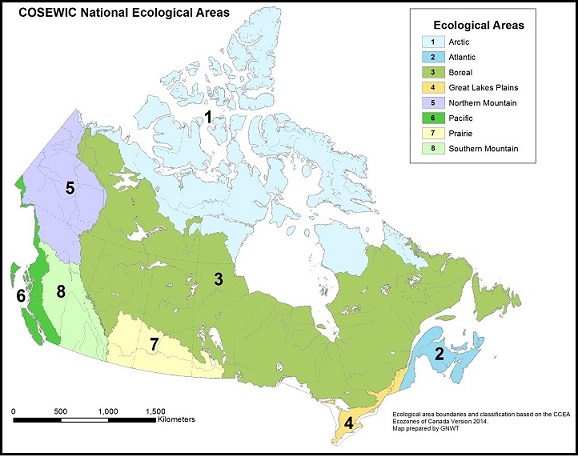

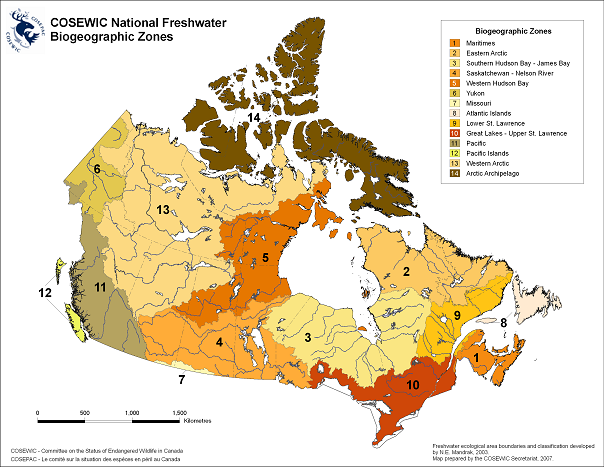

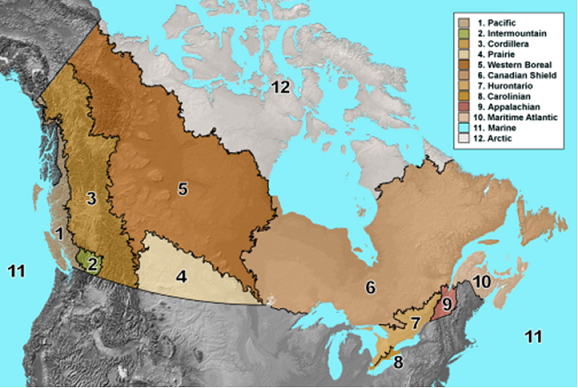

Eco-geographic boundaries can generate isolation (discreteness due to natural range disjunctions, D2), particularly for freshwater species. They also may provide evidence that can be used to clearly infer evolutionary significance because they often reflect long-term isolation (S1) and because the different ecological conditions among eco-geographic zones have been demonstrated to promote adaptive differences in the taxon (S2). The key for DU designations using geographical evidence to infer significance is that each zone has a distinct environment that can be argued to represent different selective regimes that drive "significance". Reports should rationalize the relevance of the zones in this way if they are used to support DU criteria. Some brief explanation is required in terms of the relevance of the zones to capture both past isolation and distinct selective regimes. Use the most appropriate Eco-geographic map for the Wildlife Species under consideration (examples shown in Figures 2, 3, and 4).

Where more than one DU per named species is proposed, it is important to present all available evidence for all criteria for each possible DU, including evidence that might contradict the proposed DU structure. The section (or report) discussing the proposed DU structure should clearly identify the criteria used for supporting Discreteness and Evolutionary Significance among all possible DUs considered in the report. The criteria should be referenced directly in the text and italicized. At a minimum, this section of the report should have: (1) subheadings for Discreteness and Evolutionary Significance; (2) a short paragraph for each of the corresponding arguments in F5 and a table summarizing evidence for discreteness and significance between pairs of proposed DUs (see Table 1 for an example) and, (3) a short conclusion statement. Report writers should avoid extensive discussion of the scientific evidence unless that evidence is directly relevant to the DU structure or is controversial or contradictory among sources.

Where genetic information is available, the report should summarize genetic evidence supporting the possible DU structure, but also present and acknowledge any available evidence that does not support the proposed structure. The report should also clearly acknowledge the strength of the evidence, e.g., variation in sample sizes, geographic coverage, or the type and quantity of genetic markers used among studies all affect the certainty of results. This consideration is given in light of Practical Considerations 1 (that one DU per named species is the default).

Evidence and inference regarding heritable components of traits are necessary when assessing highly plastic species that can exhibit strong morphological variation in response to environmental conditions.

Notes on Sympatric Forms

Sympatric forms of a species occur within an area when the species exhibits co-occurring, multiple forms differentiated by variation in (genetically or culturally) heritable traits (e.g., morphology, behaviour, life history, phenology, migration routes, vocal dialects) with little information flow between forms in at least one mode of inheritance (e.g., nuclear genes or cultural transmission). Evidence, or inference, of lack of information flow between potential DUs fulfils a criterion (D1) for discreteness for each form of the species. Evidence, or inference, that each potential DU possesses trait(s) that are adaptive, heritable, and cannot be recreated if the DU was lost, fulfils criteria (S2) for significance for each form of the species. If both discreteness and significance criteria are met, then each sympatric form should be considered a DU.

Species that exhibit multiple forms of traits but that have substantial natural information flow between them should not be considered sympatric forms, but rather polytypic species. In these cases, the species should be considered a single DU.

In cases where DUs existed prior to a threat or threats, followed by increased information flow subsequent to the threat(s) (e.g., the formation of a hybrid swarm due to environmental changes), the population or populations that exist should not be considered to be the original DUs as they no longer fulfil the criterion (D1) for discreteness.

Figure 1. Flow chart for assessing a pair of possible DUs within a named species. This may have to be done iteratively if there are > 2 possible DUs within a named species. See text for details.

Table 1. Modified example (from a Beluga DU report) of how to summarize pairwise differences between possible DUs. The goal is to provide all the information available, including evidence that would support the possible DUs, and available evidence that might not support the proposed DU structure. In the case of genetic data, the table would ideally distinguish between evidence from neutral genetic markers (that might support discreteness between DUs), and functional markers (that can inform evolutionary significance) and indicate both significance and effect size. Here the genetics row speaks to maternal versus biparental inheritance. This example provides some examples of evidence that might inform DU recognition. It is not intended to be exhaustive, recognizing that the available evidence and the relevant types of evidence will vary among taxa.

- Genetics: (+ = significance at P<0.05, – = nonsignificant difference, blank = no data).

- Isotopes (+ = significant difference at P<0.05, indicating focus on different prey species, blank = no data. This is an example of possible, significant phenotypic variation among DUs).

- Spatial separation (An example of evidence that could inform discreteness).

- Length at age (+ = >5% difference, blank = no data. This is an example of possible, significant phenotypic variation among DUs).

| DU2 | DU3 | DU4 | DU5 | DU6 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DU1 | 1. 1. mtDNA(+)/nDNA(+) 2. 3. All seasons(?) 4. + |

1. mtDNA(+)/nDNA(+) 2. 3. All seasons 4. + |

1. 2. 3. All seasons 4. |

1. mtDNA(+)/nDNA(-) 2. + 3. All seasons 4. + |

1. mtDNA(+)/nDNA(+) 2. + 3. All seasons 4. + |

| DU2 | 1. 2. + 3. All seasons 4. |

1. 2. 3. All seasons 4. + |

1. 2. + 3. All seasons 4. + |

1. 2. + 3. All seasons 4. + |

|

| DU3 | 1. 2. 3. All seasons 4. + |

1. mtDNA(+) 2.+ 3.All seasons 4.- |

1. mtDNA(-) 2.+ 3.All seasons 4.- |

||

| DU4 | 1. 2. 3.Summer 4. |

1. 2. 3.Summer 4. |

|||

| DU5 | 1. mtDNA(+) 2. 3.Summer 4. |

Glossary:

Figure 2. COSEWIC National Ecological Areas

Figure 3. COSEWIC National Freshwater Biogeographic Zones

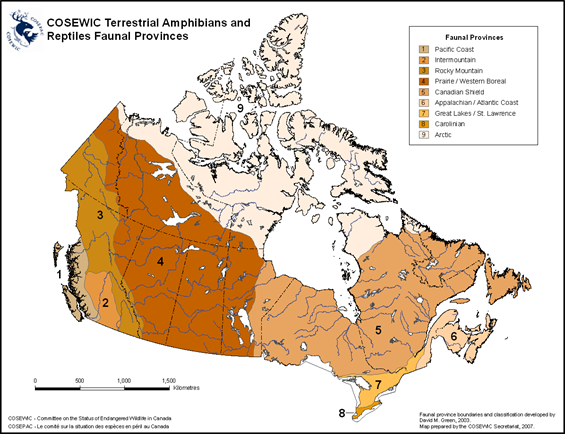

Figures 4. COSEWIC Terrestrial Amphibians and Reptiles Faunal Provinces.

Appendix

Archived Figure 4. COSEWIC Terrestrial Amphibians and Reptiles Faunal Provinces in use since at least 2007. See the Amphibian and Reptile Faunal Provinces of Canada report to COSEWIC (dated March 2016), which was part of the November 2016 discussion, for differences between this map and the current map.